The Battle of Shiloh

Wiley Sword

THE LAND WAS SOFT WITH SPRING. Tennessee was ablaze with bright sunshine, fragrant flowers, and verdant, spring green vegetation. In camp along the banks of the Tennessee River at Pittsburg Landing, 22 miles north of Corinth, Mississippi, the soldiers of Major General Ulysses S. Grant's Union Army of the Tennessee were lolling amid an idyllic setting during the first week in April 1862. Wrote one at-ease Illinois volunteer on Saturday, April 5th, "The weather here is almost as hot as August there [in Illinois] and the boys are enjoying themselves hugely, lying in the shade when off duty, barefoot, pant and shirtsleeves rolled up, collars unbuttoned and thrown open, thus presenting the most complete picture of laziness I ever saw. The timber is getting green as midsummer; the leaves are almost as thick as they will ever be, and wild flowers have gotten to be an old story."

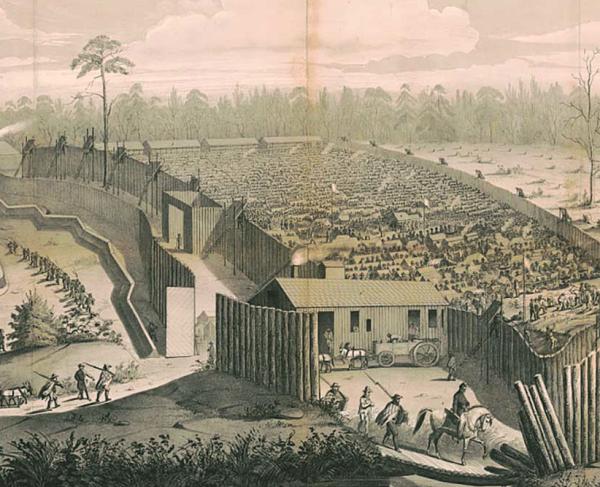

Their campground was backwoods farmland, an uneven tableland with timbered ridges and steep ravines, interspersed by plots of cleared pasture and small but mellow orchards of peach and cherry. Across a rough triangular plot of land, about three miles across at the base and bordered by Snake, Owl, and Lick Creeks, five divisions of the Union army, about 40,000 men, were comfortably if temporarily encamped. It was to be merely an offensive base, from which the combined Union forces of Grant and the Army of the Ohio - under Major General Don Carlos Buell who was then en route from Nashville would advance upon the enemy rail center at Corinth, Mississippi.

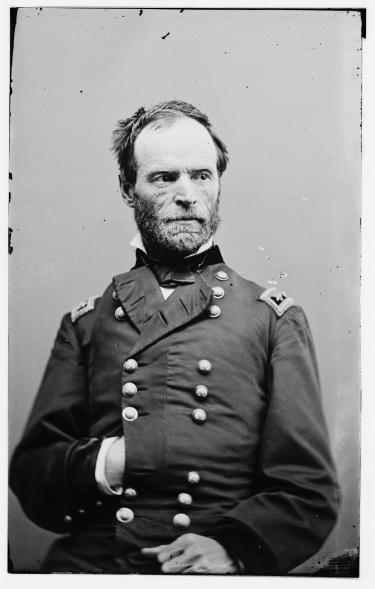

Grant's friend and subordinate, Major General William Tecumseh Sherman was the nominal commander at the Pittsburg Landing camps, since he had originally recommended the site on March 16th. Sherman had moved his division two miles inland the following day to occupy ground near Shiloh Meeting House, a rustic one room, hewn-log church. While Grant remained nine miles downriver, at Savannah, Tennessee, awaiting Buell's arrival from Nashville, Sherman's men and the army's other divisions busied themselves amid the backwoods tableland, camping, cooking, and drilling. Despite occasional fire from the pickets in the adjacent woods, and a brief skirmish on April 4th in the outlying timber, the Union army was at ease. Union Brigadier General William H. L. Wallace of Illinois had ridden out to Sherman's camp on the evening of April 5th and found "everything quiet and the general [Sherman] in fine spirits." Another Union soldier noted how the woods were filled with "Johnny-jump-ups," - wildflowers that carpeted the ground in a river of color, and at a camp in Prentiss's division a redbird appeared to serenade the idle soldiers from a black oak tree. It was a standing joke among the men that it was a Union cardinal who had enlisted in the regiment to sound reveille and retreat. Compared with what was to come, this scene could not have been more ironic or more tragic.

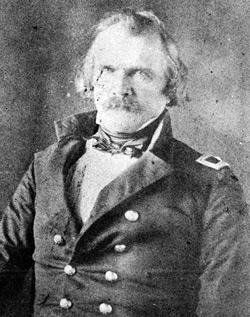

Poised at that very moment on the brink of the outer Union camps were about 35,000 determined Confederates, eager to reverse the tide of war that had resulted in key Yankee victories at Forts Henry and Donelson and led to much lost Southern territory in Kentucky and Tennessee. The Confederates were led by General Albert Sidney Johnston, the former regular army brigadier who had been Jefferson Davis's choice for top commander in the West.

Ironically, Johnston's senior subordinate, General P.G.T. Beauregard, had wanted to retreat to Corinth on April 5th, believing the enemy surely had been alerted by the noisy, delayed Confederate march over three days. Instead of being surprised, they would be found "entrenched to their eyes," he said. Beauregard was decidedly wrong.

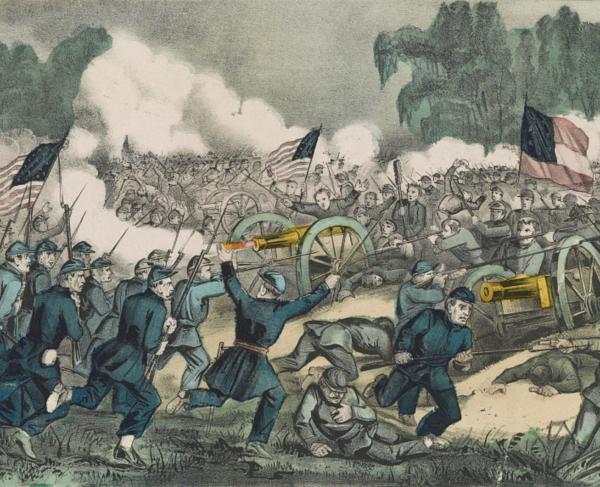

Firing began about 5 a.m. on Sunday, April 6th, initiated ironically by a Union patrol sent by Colonel Everett Peabody from Prentiss's division, which discovered Confederate skirmishers in Fraley Field, on the outskirts of Sherman's camps. Because the Union army was not expecting a battle, especially amid their own camps, many soldiers were still preparing breakfast, or engaged in camp duties when the long roll sounded, urgently calling them to arms. The dire consequences of attempting to fashion an effective defensive line on the outskirts of each division camp when nothing of the sort had been planned or even envisioned, was quickly apparent. The massed ranks of Confederates appeared about 7 a.m., and shouting the eerie "Rebel Yell," they easily overran the outer Union camps, which were without entrenchments or even good cover for shelter, many having been set up in cleared fields.

By 11 a.m. the Confederate assault, made by three corps arrayed in succeeding lines, had driven back and effectively routed Prentiss's, Sherman's, and McClernand's divisions - nearly two thirds of the total Union strength on the ground. A succession of major fields - Fraley, Rea, and Spain - had been lost to the on charging Confederates, and further disaster seemed imminent.

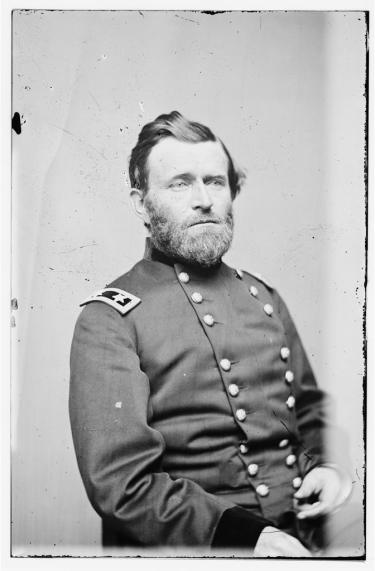

Meanwhile, Ulysses S. Grant, surprised to hear firing upriver from his headquarters at the Cherry mansion in Savannah, had belatedly rushed to the battlefield by steamboat, arriving about 9 a.m. Yet there was little he could do other than tell his commanders to hold on pending the arrival of reinforcements - Lew Wallace's division from five miles downriver near Crump's Landing, and, hopefully, Buell's advance troops, marching from the vicinity of Savannah. Clearly, Grant's Union army was in a desperate situation.

Yet the small, happenstance events at Shiloh that morning soon became the battle’s turning points. With the Confederates having routed Prentiss's division from their outer camps along the Bark Road baseline (Lick Creek area) the way was essentially open for a push straight north to Pittsburg Landing. Yet the victorious Rebels were halted by Johnston's order about 9:30 a.m., and two of the four brigades then present with him were diverted to the extreme outer right flank. By chance that morning, Confederate Captain S. H. Lockett of Major General Braxton Bragg's staff, had been sent to the far right to scout in that direction. Amazingly, he discovered Colonel David Stuart's Union brigade camp, which was beyond the deployed Confederate right flank. Fearful that the troops he mistakenly thought were a "division" would swing around and attack Johnston's flank, Captain Lockett sent an urgent message to the Confederate commander warning him of the threat. Yet Stuart's isolated brigade, only about 2,800 men, were of minimal danger. They had been posted there several weeks earlier merely to guard a bridge over Lick Creek. Alarmed by the sound of adjacent firing, they had formed in line of battle hoping to merely hold their ground. But because the pre-battle reconnaissance of the Union camps - Beauregard's responsibility - had not been effected, the Confederates had no prior knowledge of Stuart's location or existence. Johnston's plan was to roll back the Union far right flank, and Lockett's new information was deemed critical. While the two Confederate brigades under Brigadier Generals James R. Chalmers and John K. Jackson marched on a roundabout route to attack David Stuart's troops (which they easily drove back), Johnston waited for the 7,200 man-strong reserve corps under Major General John C. Breckinridge to come up.

The wait entailed more than two hours. Due to this extended delay, the routed Union troops from Prentiss's camps were able to rally and help in forming a major new defensive line in the center thickets, later known as the Hornets' Nest line. The two previously unengaged Union divisions under Generals Stephen A. Hurlbut, and William H.L. Wallace, had marched forth from their camping ground near Pittsburg Landing, and formed the essence of the critical Hornets' Nest line, connected by Prentiss's re-formed troops along a sunken road in the center. This new central line stretched about a half mile in a curving are, and provided effective cover to drive off the piecemeal-style attacks ordered by Braxton Bragg. Four separate charges led by Colonel Randall Gibson's brigade were shattered, and the angry Bragg finally witnessed the concentration of 62 artillery pieces gathered by Brigadier General Daniel Ruggles, which bombarded the tenacious Union line.

Due to the heavy enemy resistance in the Hornets' Nest, and the inability of the Confederates to attack prior to the arrival of Breckinridge's reserve corps, it was not until about 2 p.m. that Sidney Johnston belatedly organized an assault on troops holding the extreme Union left flank of the extended Hornets' Nest line. These Union troops under Brigadier General John A. McArthur were posted just east of the Hamburg-Savannah road across from the peach orchard, and held a series of steep ravines, moderately timbered but with only thin undergrowth due to the grazing of livestock. This region was to prove one of the most important sectors of the battle. Here Johnston's grand charge conducted by four Confederate brigades succeeded in driving back McArthur following fierce fighting - yet at very heavy cost. About 2:15 p.m., Sidney Johnston, riding behind Brigadier General John S. Bowen's line east of the road, was struck from behind in the bend of his right leg by a nearly spent minie ball that tore open the popliteal artery. Within about twenty minutes, Johnston collapsed and soon died from a loss of blood, the victim of a stray bullet perhaps fired by his own men. Without a senior commander on the field aware of the existing tactical circumstances, the ardor of the Confederate attacks soon withered. P.G.T. Beauregard, who remained in the distant rear, was later notified that he was the new Confederate commander; he called a halt to the fighting as darkness approached.

Meanwhile, the Hurlbut-Prentiss-W.H.L. Wallace troops in the Hornets' Nest were outflanked on opposite sides with the collapse of McArthur's men and the areas protected by Sherman and McClernand. Unable to extricate themselves from the surrounding Confederates, 2,300 Union prisoners were taken in the collapse of the Hornets' Nest, including Ben Prentiss. General William H.L. Wallace was fatally shot in attempting to escape, and by 5 p.m. the Union army was on the brink of disaster, with thousands of frightened, fugitive Union soldiers crowded in despair along the riverbank at Pittsburg Landing.

Battle of Shiloh -- Day Two

U.S. Grant was amid the chaotic scene with his last line of defense. Here ponderous siege guns originally intended to pound the Confederates into submission at Corinth were now in makeshift array about the landing and thundering at the Rebels across deep Dill Branch Ravine. Grant suddenly saw the enemy retreating - moving back by Beauregard's order - and he remarked to a staff officer, "not beaten yet, by a damn sight." The following day he would order an attack, aided by Buell's troops even then being hastily shuttled by steamboats across the broad Tennessee. Also, Lew Wallace's troops, having taken the wrong road, finally arrived about dark, and would serve to bolster the offensive.

It occurred much as Grant had envisioned on Monday, April 7th. Beauregard's troops, who had largely withdrawn to the captured Union camps to rest and refit, were taken by surprise when Union columns, spearheaded by Buell's and Lew Wallace's men, assaulted them that morning. After fierce back-and-forth fighting over ground already much bloodied on April 6th, at 3 p.m. Beauregard ordered a retreat back to Corinth. After 5 p.m. the last of the withdrawing Rebel troops cleared the battlefield, and Grant, as exhausted as his men, was content to see them go without further fighting.

The Pearl Harbor of the Civil War was over, and with it came the realization that the war would go on until one cause or the other was completely overcome. There could be no turning back now; the gruesome commitment to the war had been written in blood. Shiloh had cost the lives of 3,500 Americans amid a total of 23,800 casualties. More than 111,000 men had fought at Shiloh, and the carnage amounted to the greatest devastation known on the American continent to that date. The Battle of Shiloh had set a new, bloody standard for the world to contemplate. Today the green but hallowed ground that endures for future generations to walk and study ensures that the sacrifices made by so many will forever be remembered. "')

Wiley Sword is a retired businessman and an author, historian and collector. He is an expert on Civil War weaponry. Among his many books are: Shiloh: Bloody April and Embrace an Angry Wind, The Confederacy's Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville.